Little Brother only came out this summer, but I’m kind of assuming you’ll have heard of it, whether or not you’ve read it.

One of the things I’ve noticed since I’ve been doing this here is that there are books I expect people to have heard of and books I expect them not to have heard of. (By and large, I’m right about this. Books I think people won’t have heard of may have a few very enthusiastic fans, but I also get comments saying “Thanks for the rec.”) I approach them in a different way. If I think people already know about a book, I feel less need to introduce it before I start talking about it. I worry less about spoilers. My angle of approach is different.

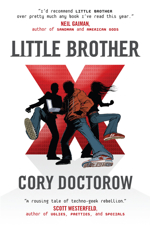

Little Brother is definitely one of the ones I think you’ve heard of. This is partly because Cory is an internet star, and it’s partly because the book had a big and well deserved push, with lots of blurbs from lots of writers (including me) and has had a lot of well-deserved attention and is a New York Times bestseller. But it’s also partly because there was a spoiler thread about it on Making Light, which makes me feel that everyone I know knows all about it.

The thing about it though is that it’s such a compelling read. The first time I read it, I literally didn’t put it down. I started reading it in bed one night and kept on reading it until 2am. This time I did manage to put it down, just about, but I still zipped through it at top speed. (It’s not as much fun reading something in manuscript as you probably think. You have to wait months to talk to other people about it, which turns out to be just as bad as waiting to read it yourself.)

There are people who don’t like first person smartass voices. I happen to be a sucker for them. Marcus is a seventeen year old hacker and the book is written in a voice of almost gleeful explanation, that just slightly patronising voice of any teenager explaining anything to any parent. Marcus is such a plausible character, too. He’s just doing so many things for the first time, in a near-future world that’s changing and becoming scarier every day. It’s a gripping edge-of-the-seat story, and it’s a lovely reading experience.

There are periods of history that seem to produce art. Sometimes they’re ages with patrons—Maecenas gathering Horace, Virgil and Ovid, the Medici Popes gathering Leonardo and Michaelangelo, John Campbell gathering Heinlein, Asimov, etc. Other times they seem to just happen, like the Romantic Poets, or happen in response to events, like the First World War poets. Yet there are huge events that don’t produce an outpouring of art. There was Second World War poetry, but I only know about it because of doing too much research. (The only person who wrote any that you may have heard of is Alex Comfort, who is of marginal SF relevance because of his ghastly Tetrarch, and of general interest because of The Joy of Sex.)

It seems to me that recent world history, depressing as much of it has been to live through, is one of those events that is evoking art. Some people might decry the gloom of SF, but it seems to me that we’re having an outpouring of really interesting and relevant politically motivated art that we wouldn’t have had without it. Spartan. Never Let Me Go. Little Brother seems to be a terrific example.

There are, of course, a couple of problems with politically motivated art. Firstly, undigested politics makes for lumpy stories—and I find this a worse problem when I do agree with the politics than when I disagree. Secondly, some people disagree with the politics so vehemently that they can’t read the story for it, even if the writer has digested it enough, and likewise, there are people who agree so much that they’ll overlook the fact that something is the most awful crap.

For me, in my personal opinion, Doctorow knows what he’s doing with the story he’s telling. He doesn’t let the politics—though they are overtly a part of it—get in the way of the characters or the story.

But it is definitely a fantasy of political agency. It’s about a teenager growing up in San Francisco on what’s clearly the day after tomorrow. He feels like a teenager, but he does change the world. When I was thinking about what Bujold meant I thought of this right away. It’s a plausible story in the sense that I buy every moment of it leading from every other moment when I’m reading it, I have no suspension of disbelief issues, but when I stop to think now about whether one person—one kid—could achieve all that

But it’s a great page-turning read. I suspect that in future times, in one of those great ironies, it’ll be assigned reading in schools, and the kids reading it will think they’re reading about 2008—and they almost will. Meanwhile, do read it if you haven’t yet.

Little Brother is a great read and makes me wish that it could have been made into required reading for this election year – and not just for school – for everyone.

After reading Little Brother all I could say was “Man I’m glad I read the free edition and didn’t pay for this garbage”.

The book was obviously meant to be a treatise on the US in 2008, but not the US that really exists, but instead the one that delusional members of the hard left think exists, and its politics and heavy-handed message were the entire point. That the totalitarian environment that lefties like to imagine doesn’t exist here is self-evident. The fact that they can rant like they do, and Doctorow can publish his diatribe is proof of this.

This is the only book in a long time that I got my 13 year old son to read voluntarily. He was so charged up and excited by it. I read it afterwards and I had a lump in my throat the whole time. My daughter and son-in-law both loved it enough to get their own copy and my daughter has lent it to the English teacher at the high school she where she teaches.

I thought it was one of the most powerful books I’ve ever read. It was right up there with “To Kill a Mockingbird” for me.

Not to overlook High Flight – 18 August 1941 – then too lots of songs, including official/semi-official/popular and much filk equivalent that never achieved wide currency – I suspect because needing too many footnotes for an audience that wasn’t there.

In my opinion there is great WWII graphic art starting perhaps with Guernica.

One of the strengths of Little Brother for me is SF back in the gutter where it belongs. This is not Holden Caulfield.

That is on the one hand what could properly be called cardboard characters and on the other hand be praised as evoking a character in a phrase – because stereotyped but myths and mythic charactes are cliches because they are so often true.

@@@@@ Someone Else: I agree the political stance of the novel is pretty obvious, but I think Doctorow tempers the extremist leanings of the young narrator with tangible consequences for his actions. Mikey rebels against the government, but he’s got to accept the ramifications of being a rebel. He’s got to wrestle with who he is and what his actions are turning him into — not just in his eyes, but the eyes of his friends, family, society, and government. That, beyond anything else in the novel, is what’s important and what makes it great: the fact that Mikey questions himself just as much as he questions the world around him. An important lesson regardless of which side of the political divide you fall on.

@@@@@ 5

Exactly right. I also loved that when Mikey is trying to do something positive, something he thinks will work and help dismantle the system, he sometimes winds up making things worse and reinforcing those systems. His actions backfire and he’s not just a big hero (a big peeve of mine in YA).

I felt it had one of the most authentic young adult voices I’ve ever read. Mikey alternates between being overly confident and insecure, and though he makes smart choices he often lacks the perspective to know some of the consequences of his actions. Yet he’s genuine and sincere, idealistic almost to a fault, and I want to be his friend.

I tend to lean a little right of center politically. I did not see this as a leftist novel. On the contrary, I think it’s very much a libertarian work. Since when is standing up for the Bill of Rights strictly a leftist thing?

I think part of why this worked for me was my own memories of being a teenager in the aftermath of Watergate. We were absolutely convinced that the FBI had files on everybody. If you subscribed to certain publications or participated in certain groups, you had to be on some sort of FBI watch list. Looking at history, I think this may have been a reaction to McCarthyism twenty years earlier. Modern technology has made it even easier to keep track of people. I don’t think it’s either a liberal or conservative stance to think that the government has no business treating citizens like criminals without reasonable suspicion. In “Little Brother”, there was no reason for Marcus and his friends to be denied their constitutional rights and detained by Homeland Security. They were truants, not terrorists.

As a mother of a teen and a twenty-something, I imagined what it must have been like to be Marcus’s mother. We mothers don’t know everything that our kids are doing and we know that we are out of the loop. I felt like I was helplessly watching my own son.

This book worked for me on a lot of level. None of them were left-wing politics.

Huh. I wrote about this book on my blog because I was so disappointed by it. I came to it expecting to like it and knowing ahead of time that I agreed with most of the politics, but was pretty severely turned off by several things.

1) It’s depressingly one-sided. There is no one (aside from the jack-booted DHS thugs) that strongly articulates a view opposite Marcus, and the token opposition he gets from his dad, for example, is quickly overcome. It is blatantly asserted that Good Guys can only be on the side of Marcus.

2) The terrorist attack itself is completely ignored after it happens. The DHS goes immediately to harassing Marcus & co., and Marcus doesn’t even once stop to wonder who the real terrorists were. IOWs, the real conflict between security and freedom is never explored. It is, instead, treated like it doesn’t exist.

3) Several of Marcus’s tricks are not just illegal, but immoral and deeply disruptive of the lives of innocent people around him. Insofar as he recognizes it at all, the blame is entirely apportioned to the DHS.

Basically, Marcus is Doctorow’s Mary Sue in a fantasy story where hackers save Truth, Freedom, and the American Way from the eeevil government.

“Marcus is a fourteen-year-old”?

Marcus is seventeen.